Chapter 16: "Victory Gardens"

As the 1930's gave way to the '40's, things seemed to be going reasonably well at Wyandot. With The Great Depression having finally run its course, the country's improved economic outlook boded well for the club's fortunes. Despite the economic turmoil of the decade past, Wyandot had successfully established itself as a mid-priced no-frills golf club with an outstanding course and a stable of excellent low-handicap players, both male and female. But a potential threat to Wyandot's continued existence always loomed given that the club was merely a tenant in a series of short term leases with its landlord, the Glen Burn Partnership.

With the club's patron John W. Kaufman gone, Wyandot was dependent on the continued benevolence of the remaining Glen Burn partners including Harold Kaufman, Oscar "Dutch" Altmaier, and perhaps other beneficiaries of the John Kaufman estate. Harold enjoyed a long history with the club having chaired the club's construction committee that built the Donald Ross- designed golf course. He remained active in the club, still serving on the club's board of directors. Harold probably would have been satisfied with continuing the "nominal" rent originally arranged by his father with the club in 1931. But it is unlikely that Harold's partners enjoyed the same level of allegiance to Wyandot. One or more of those partners must have grown frustrated with the paltry revenue generated from their tenant, and Harold may have been under pressure to remedy the situation. Even before the war, Harold Kaufman was urging club members to buy the property from Glen Burn. Dwight Watkins tells this story: "My father Cy was a Wyandot member in those days. He told me that Kaufman approached the members several times saying, 'you fellows have to buy it or else we'll have to sell to someone else!' No one believed him because Mr. Kaufman already had plenty of money."

However, the financial difficulties of clubs like Wyandot soon seemed trivial once the country plunged into war on December 7, 1941. Far more than any other war this country has fought, World War II received unqualified popular support. Most agreed that all activities on the home-front must by necessity take a backseat to the goal of obtaining victory. While the advent of the war presented hardships for all leisure-related activities, golf clubs and courses encountered the greatest challenges by far. They were broadsided from every direction. In retrospect, it is a wonder that most of them survived the war.

The hits to the business of golf were pervasive and far-reaching. The first was the Office of Price Administration's ("OPA") edict ordering the rationing of automobile tires in January, 1942. This measure was designed to discourage motorists from pleasure driving to places like golf courses. Then, in May, 1942, the OPA ordered the discontinuation of golf ball manufacture for the duration of the hostilities. But the hardships caused by those measures paled in comparison to those caused by the imposition of nationwide mandatory gas rationing, effective December 1, 1942. Most motorists were limited to the purchase of three gallons of gasoline per week! This mandate presented an enormous dilemma for all clubs and courses. With such a severe gas consumption limitation, how could golfers get to their respective courses- particularly those more remote "country" clubs located several miles from the centers of population?"

Wyandot did its best to address gas rationing. The club formed a transportation committee to figure out how to get its golfers to the course with "a minimum of gas and rubber consumption." The Columbus Dispatch noted that the committee was engaged in working out the details of a "share the ride" program, "but if this should prove inadequate, the committee might resort to horse-drawn vehicles, or a station wagon from the High Street car line to the course." Rationing also caused a predictable reduction in dining and other use of Wyandot's facilities. The Dispatch noted that "dinners will be discontinued to be replaced by light luncheon service."

Even assuming a golfer expended his precious rationing coupons to reach the course, who was going to carry his clubs? Golf carts would not come into general use until 1951. The supply of professional caddies had dwindled down to a handful, as most had entered the service or related essential industries. The concept of carrying one's own clubs was an alien one to most club members- a point well-made by Byron Nelson, then the professional at Toledo's Inverness Club. "Lord Byron" offered the view that, "country club golfers simply won't play if they have to carry their own sticks."

It took awhile for the affects of the draft to be fully felt by Wyandot, but by the spring of 1943, most of the male membership, age 38 and below, were either in military service or engaged in essential industries. War Manpower Commissioner Paul McNutt affirmed in February, 1943 that "by the end of this year 10 out of 14 of the able-bodied men between 18 and 38 will be in the armed services." Another blow was struck that month when McNutt issued an order effective April 1, 1943 listing the various job occupations that would be classified as "non-essential." Those men so engaged were required to find "essential" work or be drafted. Among the positions considered non-essential was that of a "greenkeeper." Thus, most courses were depleted of their crewmembers unless they were over the maximum draft age. Wyandot's greenkeeper Lawrence Huber was already 52 years old and well beyond draft eligibility. Still, he harbored a patriotic urge to serve his country, so in the spring of 1943, Huber left Wyandot and accepted a position maintaining military airfields for the Corps of Engineers. Lawrence's son Jim Huber recollects that his dad may have had a second reason for leaving Wyandot. According to Jim, his father believed that the club was in a precarious position, and that there was a good chance the course would ultimately become publicly owned. Lawrence acknowledged to his son that he was "spoiled" by the care that country club players give their course (replacing divots and repairing ball marks etc.) which public course players often eschew. Lawrence had no interest in superintending anything other than a private club course.

Wyandot's professional of 12 years, Francis Marzolf, also left the club, taking a position managing military housing units in Columbus. The club, saving expenses wherever possible, decided not to replace him for the time being, electing to get by solely with a sales person in the pro shop.

With the loss of membership causing a corresponding loss of revenue (most clubs estimated that gross revenues were down 50%), Wyandot could afford only the barest of skeleton crews. Thus, a "share the work" program was instituted by which the remaining members would run the club themselves. Ten committees were established to "plan the 1943 season, meet all of the emergencies, and maintain golf and golf facilities."

Some sports could afford to place their facilities in mothballs and await a successful conclusion to the war. Russ Needham of the Dispatch wrote frequently on this subject and made the point that the decision to discontinue golf course maintenance meant the loss of the course. "There won't be a golf course as such, there anymore. It'll just be pasture, fit for growing corn and potatoes perhaps, but you can't putt on pasture, and you can't blast out of a bramble bush......If they [the golf clubs] let their course go unkempt for a season, or even a month or so, at the critical time of year, the greens will be gone beyond all redemption....Replacing a green of average size would cost in the neighborhood of $1,000. That's one green and there are 18 on a golf course.....So, the problem of the golf clubs is, shall they suspend, as most sports could if necessary? If they do it means an expense of upward of $25,000 to rebuild them in that glorious day after victory. Or do they keep them up as best they can, gambling the expense now will be less than to rebuild later. And if they decide on this, who'll do the work and who'll pay for it?"

This was a dilemma faced by even the most prestigious clubs. Augusta National dealt with the issue in part by allowing a herd of cattle to roam the course in hopes that the cows' grass munching would stay ahead of the growth of the turf.

Once on the course, club golfers faced further obstacles that were arguably more oppressive than all the others: guilt and derision! Golfers were often made to feel unpatriotic by indulging in a rich man's pastime while U.S. soldiers were fighting and dying overseas. "Don't you know there's a war on?!" was a common refrain heard by those engaged in recreational pursuits, and especially golfers.

The Dispatch's Russ Needham, in a column sympathetic to stigmatized golfers, referenced one of Wyandot's players to illustrate the club player's plight. "Bill Margraf, whose rich locker-room baritone should not be lost in the turmoil, come what may, is a little dismayed at the prospect of what the summer will bring...Bill feels a little timid about taking his spoon or mashie in hand... Bill flinches to think how he'll feel if, as he tees off No. 4, which is near the highway, some blighter will be coming down Morse Rd.- on very vital business of course, and shouts 'slacker' into his sensitive ears."

That stigma reached high into the ranks of the professional golfers as well. The PGA suspended most tournament operations in 1943, conducting only 3 events. Most of the pros were in service or working for essential industries for the duration. Denny Shute came back to Columbus, and performed his service working as an inspector for Jeffrey Manufacturing.

Denny Shute with Jeffrey Manufacturing

Denny and his wife settled down in a farmhouse with ten acres located on Hard Road on the northwest side of Columbus. When not engaged with Jeffrey, Shute busied himself with chores.

Denny Shute on his farm

Shute still managed a weekly game in the Columbus Golf League as the ace player on the King-Taste team. During wartime, the league permitted each team to have one professional. Imagine having to go head-to-head with a three-time major champion without strokes!

Other local pros also were employed with essential industries. Brookside's Herb Christopher spent the war in the personnel department of Curtiss-Wright, a military aircraft manufacturer.

Herb Christopher, while at Curtiss-Wright

Wyandot and the other clubs searched for ways to maximize revenue while still contributing to the war effort. The club instituted the category of "governmental memberships." This was viewed by the Dispatch as a "combination of thoughtful hospitality and a desire for self-preservation." Such memberships were reserved for males "not resident but temporarily located in Franklin County." The new membership category was designed to garner new members from essential industry employees and men in the armed services. The dues for this new category were set at $10 per month with no initiation fees. Wyandot's president, Paul Anderson was cautiously optimistic stating that "our membership drive is exceeding expectations." York Temple adopted a $10 membership fee with the proviso that the member would have to pay a 30 cent greens fee for each round played.

Halfway through the summer of '43, the clubs and the CDGA began to find ways to contribute to war relief through tournament competition. All of the clubs in the Columbus district sponsored "Hale America" golf events over the July 4th weekend to benefit the Red Cross. On July 18th, the CDGA saw fit to hold its first competition of the season- a mixed two-ball foursome event at Columbus with all entry fees likewise being donated to the Red Cross.

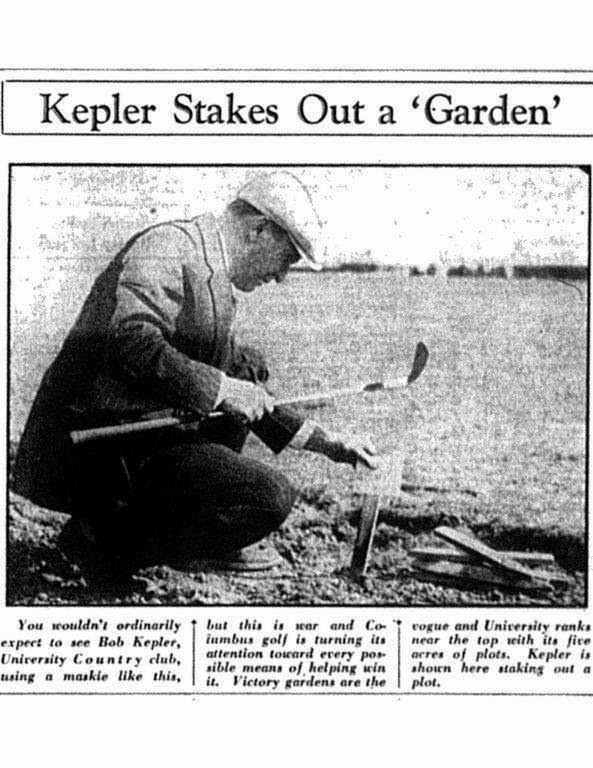

Another means by which the clubs contributed to the war effort were the numerous "victory gardens" planted in their spare space. The gardens were used to plant vegetables, fruit and herbs with the intent of reducing pressure on the public food supply. Maintenance of these gardens also helped boost the morale of those tending them. Every private club in the Columbus district established a victory garden, and this produced a spirit of friendly competition to determine which club's garden was the best. Columbus and Scioto plowed and planted four acres. Wyandot reserved plots for 60 members over 5 acres. Brookside boasted the largest garden with seven acres cultivated. That club even hired a man to "pitch a tent on the course and do night patrol duty in the 'victory garden' areas."

Despite these burdens, there was still some stellar golf played by Wyandot members during the war years. The men's club team won the season- long inter-club competition in 1941. Johnny Florio, now 35, shot a 64 at his home course on July 4, 1944 tying Francis Marzolf for the second lowest tally scored at Wyandot. Two other notable amateurs- Ray Heischman and Byron Jilek- joined the club for brief periods. Jilek, an amazingly consistent ball striker, was a particular standout. From 1933 to 1936, he played for Miami University's golf team, serving as captain his senior year. Before moving to Columbus, he won Zanesville Country Club's championship. He was good enough to match up in exhibitions with the likes of Byron Nelson and Chick Evans. Upon moving to Columbus in 1942, he joined Wyandot, and made a run at winning the District Amateur that year before bowing out in the semi- finals. But Jilek did not stay long at Wyandot, moving over to York Temple in 1944. His exodus may have been the result of constant rumors that the course's grounds were about to be sold to the State of Ohio. Jilek enjoyed a distinguished career in local golf circles, winning the District Amateur, the first of his three District Amateur titles, in 1947. He ultimately left York Temple for Brookside, and became a many-time club champion there.

Unfortunately, there was a factual basis underlying the ongoing gossip surrounding the club's sale. Negotiations between the Glen Burn Partnership and the State of Ohio were heating up. It is reasonable to assume that the financial hardships caused by the war had further compromised Wyandot's ability to make rental payments to Glen Burn. But was Glen Burn motivated to sell because it wanted rid of an investment that was not working out, or was it because the state (as intimated in a Russ Needham column in the Dispatch) was threatening to initiate condemnation proceedings anyway, and that partnership resistance to governmental acquisition would be futile? Or both? Given the prior repeated efforts of Harold Kaufman to divest the property to the club's members, all of these rationales are plausible.

In July, 1944, Glen Burn sold the entire property to the State of Ohio for $100,000. The State desired to replace the existing Hogwarts-like State of Ohio School for the Deaf, located on Town Street in downtown Columbus with an up-to-date facility.

State of Ohio School for the Deaf in downtown Columbus

The State was also seeking land for the State of Ohio School for the Blind, then located on Parsons Avenue in Columbus. The Wyandot property would allow each school to maintain its own separate campus on either side of the gorge.

State of Ohio School for the Blind, Parsons Avenue, Columbus

As the transaction with the State loomed, Russ Needham lamented the anticipated passing from the scene of the wonderful Wyandot course. But it wasn't the only golf property on the chopping block. It appeared that Indian Springs and Brookside were also soon to be sold. The latter course had become the target location for the new state Fairgrounds. Needham commented that Brookside's remote location "in these transportation-ridden days, is unfortunate. Its chief assets are a fine and enthusiastic membership and a delightful clubhouse, although the golf course itself is inclined to be on the monotonous side. It might be, in some distant day, the members of Wyandot and Brookside, backed by the funds they will receive for their clubs, will see fit to get together, buy land in some new location and restore the best features of each club into one sterling organization." (Brookside was never acquired by the State and it survives to this day as one of the city's finest courses).

But Needham was clearly saddest about what appeared to be the imminent closing of Wyandot. Waxing eloquently, he described the beloved track this way: "It wasn't long and it wasn't difficult, as long as you kept it straight. But it was a delight to play. It was like a cool soothing hand on a fevered brow on a hot day. It had calmness and dignity combined with a suggestion of the joy of living. There were few golf courses like it. It's a shame it has to go."

But despite the sale, Elks'- Wyandot's story was not at an end. There would be several more episodes in the course's narrative.

Acknowledgements: Dwight Watkins, Tom Marzolf, Archives of the Columbus Metropolitan Library, Columbus Memory, Scripps-Howard Newspaper/Grandview Heights Public Library/ photo.org collection http://www.photohio.org ; Russ Needham, Kaye Kessler, and the Columbus Dispatch; Wikpedia

No comments:

Post a Comment